Graphics for this handout were developed by Jordan Golembeski.

This handout explains prepositions that express movement toward something: to, onto, and into. First, the prepositions will be introduced as a group. Then, the special uses of each one will be discussed.

To, into, and onto correspond respectively to the prepositions of location at, in, and on. Each pair can be defined by the same spatial relations of point, line/surface, or area/volume. To learn more about the spatial relationships expressed by these pairs of prepositions, read the first section of "Prepositions of Location: At, On, and In" before you start reading this handout.

Introduction

The basic preposition of a direction is "to."

TO: signifies orientation toward a goal

When the goal is physical, such as a destination, "to" implies movement in the direction of the goal.

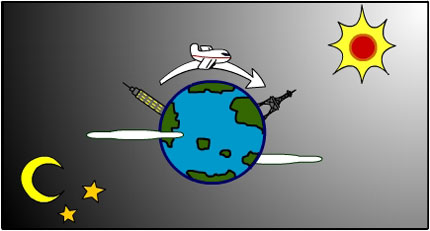

We flew from New York to Paris. (OR) We flew to Paris.

When the goal is not a physical place, for instance, an action, "to" marks a verb; it is attached as an infinitive and expresses purpose. The preposition may occur alone or in the phrase in order. The two uses can also occur together in a single sentence:

The other two prepositions of direction are compounds formed by adding "to" to the corresponding prepositions of location.

The preposition of location determines the meaning of the preposition of direction.

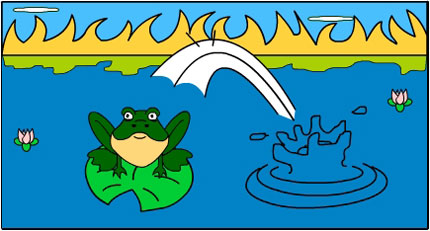

ON + TO = onto: signifies movement toward a surface

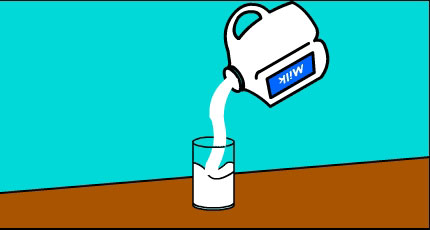

IN + TO = into: signifies movement toward the interior of a volume

("To" is part of the directional preposition toward, and the two mean about the same thing.)

The frog jumped onto the lilypad.

The milk went into the glass.

With many verbs of motion, "on" and "in" have a directional meaning and can be used along with "onto" and "into."

This is why "to" is inside parentheses in the title of the handout, showing that it is somewhat optional with the compound prepositions. Thus, the following sentences are roughly synonymous:

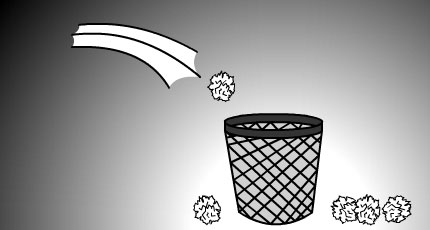

The paper went into the garbage can.

The crab washed up onto the shore.

To the extent that these pairs do differ, the compound preposition conveys the completion of an action, while the simple preposition points to the position of the subject as a result of that action. This distinction helps us understand how directional and locational prepositions are related: they stand in the relationship of cause and effect.

The paper went into the garbage can.

Position of subject: the paper is in the garbage can.

The crab washed up onto the shore.

Position of subject: the crab is on the shore.

See the sections below for some exceptions to this rule.

Uses of "To"

"To" occurs with several classes of verbs.

Verb + to + infinitive

Verbs in this group express willingness, desire, intention, or obligation.

Willingness: be willing, consent, refuse

Desire: desire, want, wish, like, ask, request, prefer

Intention: intend, plan, prepare

Obligation: be obligated, have, need

Examples:

I refuse to allow you to intimidate me with your threats.

I'd like to ask her how long she's been skiing.

I plan to graduate this summer.

Henry had to pay his tuition at the Bursar's office.

In other cases, "to" is used as an ordinary preposition.

Verbs of communication: listen, speak (but not tell), relate, appeal (in the sense of 'plead,' not 'be attractive')

Verbs of movement: move, go, transfer, walk/run/swim/ride/drive/ fly, travel

Except for transfer, all the verbs in listed here can take toward as well as to. However, "to" suggests movement toward a specific destination, while "toward" suggests movement in a general direction, without necessarily arriving at a destination:

The plane was headed toward a storm cloud.

Additional examples:

(It was headed in the direction of a storm cloud; it may not have reached or flown through the cloud.)

The golf ball rolled toward the hole.

(Drive in the direction of the city limits; turnoff may be before arriving there.)

(I actually want to arrive at the airport.)

Uses of "Onto"

"Onto" can generally be replaced by "on" with verbs of motion.

The hat went on(to) his head.

Dietrich jumped on(to) the mat.

Huan fell on(to) the floor.

Athena climbed on(to) the back of the truck.

Some verbs of motion express the idea that the subject causes itself or some physical object to be situated in a certain place (compare the three example directly above).

Of these verbs, some take only "on." Others take both "on" and "onto," with the latter being preferred by some speakers.

He put the socks on his feet.

The plane landed on the runway. (not "onto" the runway)

Sam hung the decoration on the Christmas tree. (not "onto" the tree)

He placed the package on the table. (not "onto" the table)

Joanna spilled her Coke on the rug. (not "onto" the rug)

Samir moved the chair on(to) the deck.

The crane lowered the roof on(to) the house.

The baby threw the pot on(to) the floor.

Verbs taking only "on" are rare: "set" may be another one, and so perhaps is "put." Other verbs taking both prepositions are "raise," "scatter" (when it takes a direct object), "pour," and "add."

The farmer scattered seed on(to) the fertile ground.

We're adding on a wing at the back of the building.

We're adding a porch onto the house.

In "We're adding on a wing at the back of the building," "on" is really part of the verb, while in "We're adding a porch onto the house," "onto" is a simple preposition. This contrast points to a fairly important and general rule:

Simple prepositions can combine with verbs, but compound prepositions cannot.

Note also that in "The farmer scattered seed on(to) the fertile ground", the word "on" has its ordinary meaning of a position on a surface, but in this case the surface is vertical rather than horizontal— the side of a building.

There are a number of verb-preposition combinations that are similar to "add on" but have the meaning "of continuing or resuming an action" when used in the imperative mood.

Except for "hang," which takes both "on" and "onto," the following verbs all occur only with "on." The meanings of these combinations, some of which are idiomatic, are given in parentheses. Not all of them have the force of a command.

- Hang on / Hang onto the rope ("continue to grasp tightly")

- Carry on ("resume what you were doing")

- Sail on ("resume or continue sailing")

- Dream on ("continue dreaming"; a humorous way of saying "that is an unattainable goal")

- Lead on ("resume or continue leading us")

- Rock on ("continue playing rock music")

Drive on! (Or, Keep driving toward the city).

Uses of "Into"

With verbs of motion, "into" and "in" are interchangeable except when the preposition is the last word or occurs directly before an adverbial of time, manner, or frequency.

In this case, only "in" (or "inside") can be used.

Spike is lying in his house. (Not into.)

The patient went into the doctor's office. The patient went in. (not "into")

Our new neighbors moved into the house next door yesterday. ("to take up residence in a new home'")

Our new neighbors moved in yesterday.

In "Our new neighbors move in yesterday," the last word is the time adverbial yesterday, so the object of the preposition in can be omitted. Of course, in an information question, "into" also can be last word except for an adverbial when its object is questioned by a wh- word:

Now what kind of trouble has she gotten herself into?

Now what sort of trouble is she in?

Verbs expressing stationary position take only "on" or "in" with the ordinary meanings of those prepositions.

If a verb allows the object of the preposition to be omitted, the construction may have an idiomatic meaning.

The cat sat on the mat.

The doctor is in his office.

The doctor is in. ('available for consultation')

"In(to)" has two special uses with "move."

When "move in" is followed by a purpose clause, it has the sense of "approach."

The lion moved in for the kill.

The police moved in to rescue the hostages inside the building.

In "The lion moved in for the kill" and "The Police moved in to rescue the hostages inside the building," "in" is part of the verb, so "into" cannot be used. We cannot say: "The lion moved into for the kill."

When "into" is used with move, it functions as an ordinary preposition to convey the idea of moving something from one place to another.

A man is jumping into the pool.

The man is in the pool.

The person is placing groceries into the shopping bag.

The person has completed putting groceries in the bag.

Credit: Purdue